31282 and 32571 - Summary

1. Software Testing and Quality Assurance

Software Quality and Software Quality Assurance (SQA)

- Software quality is often a moral and legal requirement.

- Quality (almost) always comes with a cost.

- Cost Categories:

- Prevention Costs: Training, planning, early reviews/testing.

- Appraisal Costs: Inspections and testing.

- Failure Costs: Rework, complaint handling, loss management.

Software Quality

- 3 different terms of software quality issues:

- Errors: An error is something in the static artefacts of a system that causes a failure.

- ex: Syntax error

- Defect/Fault: A defect or bug is a situation at runtime where some underlying error has become reflected in the system's runtime state.

- ex: Incorrect condition in logic

- Failure: A failure is any deviation of the observed behaviour of a program or system from the specification.

- ex: Software's working, but fail/lag during the runtime

- Errors: An error is something in the static artefacts of a system that causes a failure.

Measuring Software Quality

- Technical Quality Parameters

- Correctness: Defect rate

- Reliability: Failure rate

- Capability: Requirements coverage

- Maintainability: Ease of modification

- Performance: Speed, memory, and resource efficiency

- User Quality Parameters

- Usability: User satisfaction

- Installability: Installation experience

- Documentation: Clarity and usefulness of manuals

- Availability: System uptime and access

- Quality Models and Standards

- McCall’s Quality Factors: Operation, Transition, Revision

- Standards: ISO/IEC 90003:2018, CMMI

Software Quality Assurance (SQA)

- SQA is a structured set of activities to ensure both the software product and its development process meet functional, technical, and managerial requirements.

- Objectives:

- Prevent defects early in development

- Improve development and maintenance efficiency

- Ensure alignment with quality goals

Three Principles of SQA

-

Know What You Are Doing: Understand current system state and project progress. Maintain clear reporting, structure, and planning.

-

Know What You Should Be Doing: Maintain and track up-to-date requirements and specifications. Use acceptance criteria, prototypes, and user feedback.

-

Measure the Difference:Use tests and metrics to compare actual vs. expected performance. Quantify quality (e.g., percentage of passed test cases).

SQA Environment Considerations

- Contractual Requirements – Timeline, budget, functional scope

- Customer-Supplier Relationship – Active collaboration and validation

- Team Collaboration – Diverse skills and mutual review

- Inter-team Cooperation – External expertise and project division

- System Interfaces – Interaction with other software systems

- Team Turnover – Knowledge transfer and onboarding

- Software Maintenance – Long-term operational quality

Software Quality Models

McCall's Quality Factors

McCall’s model categorizes software quality into three main perspectives:

- Product Operation: Correctness, Reliability, Efficiency, Integrity, Usability

- Product Revision: Maintainability, Flexibility, Testability

- Product Transition: Portability, Reusability, Interoperability

These factors are depicted as branches of a tree, emphasizing how they contribute to "Quality Software."

Boehm's Software Quality Tree

Boehm’s model uses a hierarchical quality tree structure with characteristics such as:

- As-is Utility: Portability, Reliability, Efficiency, Usability (Human Engineering)

- Maintainability: Testability, Understandability, Modifiability

Each characteristic further breaks down into attributes like Robustness, Consistency, Accuracy, etc., showing interrelated quality aspects.

ISO/IEC 9126

ISO/IEC 9126 defines six high-level quality characteristics for software:

- Functionality

- Reliability

- Usability

- Efficiency

- Maintainability

- Portability

Each characteristic answers key questions such as “How easy is it to use/modify/transfer the software?” or “How reliable is the software?”

Dromey's Quality Model

Dromey’s model links product properties with quality attributes and focuses on how implementation affects software quality.

- Product properties: Correctness, Internal, Contextual, Descriptive

- Quality attributes: Functionality, Reliability, Maintainability, Efficiency, Reusability, Portability, Usability

This model provides a constructive framework that emphasizes the role of implementation.

ISO 9128

ISO/IEC 25010 is an evolution of ISO 9126 and provides a more detailed breakdown of quality factors and sub-factors:

- Functionality: Suitability, Accuracy, Interoperability, Compliance, Security

- Reliability: Maturity, Fault Tolerance, Recoverability, Compliance

- Efficiency: Time behavior, Resource behavior, Compliance

- Maintainability: Analyzability, Changeability, Stability, Testability, Compliance

- Portability: Adaptability, Installability, Co-existence, Replaceability, Compliance

- Usability: Understandability, Learnability, Operability, Attractiveness, Compliance

2. Software Testing and Processes

Software Testing

Verification vs. Validation

- Verification – Confirms that the software meets specified requirements

- Validation – Ensures the developed software meets user needs and expectations

Relational:

- Verification without Validation = Perfect implementation of the wrong solution

- Validation without Verification = Right idea, broken execution

- Both Together = Quality software that actually helps users

V-model

| Development Phase | Corresponding Test Phase |

|---|---|

| Business Requirements | User Acceptance Testing |

| System Requirements | System Testing |

| Architecture/Design | Integration Testing |

| Program Specification | Unit Testing |

| Coding | (Implementation phase) |

Types, Techniques, and Levels of Testing

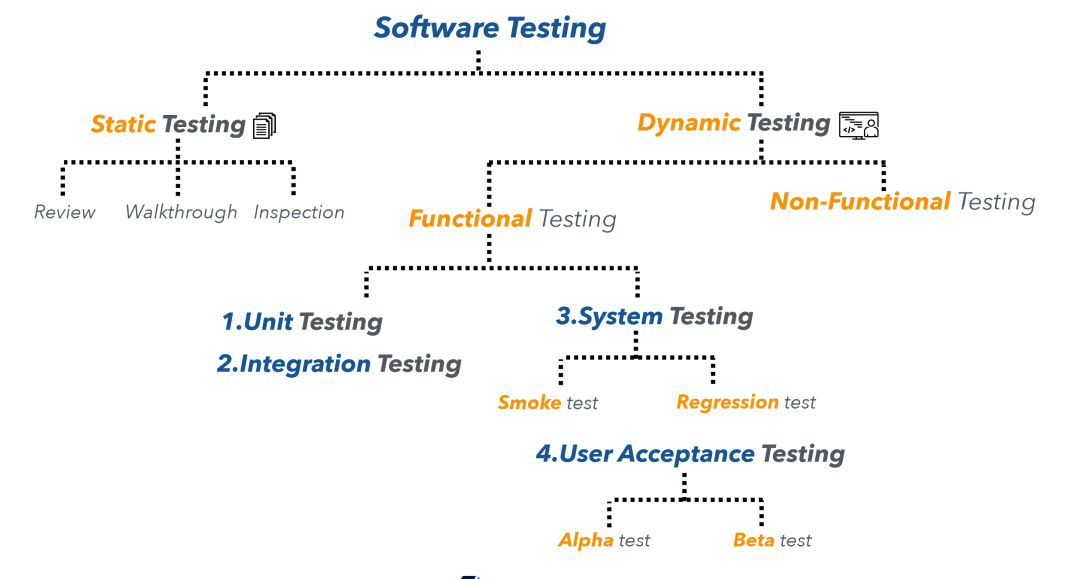

Static and Dynamic Testing

- Static Testing – Conducted without executing the program (e.g., inspections, analyses, documenting).

- Dynamic Testing – Involves executing the program to observe outputs.

Functional and Non-Functional Testing

- Functional: What the system does

- Login functionality

- Calculation accuracy

- User registration

- Data processing

- Non-Functional: How the system performs

- Speed, security, usability, reliability

Levels of Testing based on system abstraction

- Unit Testing (On: Code) – Individual components are tested independently to ensure their quality. Focus to detect error on:

- Data structure

- Program logic and program structure

- Interface

- Functions and operations

- Integration Testing (On: Design) – A group of dependent components are composed and tested together. Objectives to detect errors in:

- Software architecture

- Integrated functions or operations

- Interfaces and interactions between components

- System Testing (On: Requirements) – Tests the overall system (both hard- & soft- ware) if they meet the requirements. Objects:

- System input/output

- System functions and information

- System interfaces with external parts

- User interfaces

- System behavior and performance behavior and performance.

- Acceptance Testing (On: What users really need) – Confirms the software meets customer needs and expectations.

(Unit) Testing Techniques

- Black Box – Based on input-output behavior without internal code knowledge.

- White Box – Focuses on internal code paths and structures.

- Grey Box – Partial knowledge of internal code is used.

Testing in Software Development Lifecycle

- A software process is a framework that guides the planning, development, testing, and delivery of software.

- Common models include:

- Waterfall (sequential stages)

- Agile (iterative and incremental)

- V-Model (verification and validation aligned)

- DevOps (continuous integration and delivery)

Software Processes and Their Role in SQA

- Software development includes:

- Requirements → Specification → Design → Code → Testing → Maintenance

- Testing is a continuous activity throughout the lifecycle:

- Core Activities:

- Specification: Define requirements

- Development: Build the product

- Validation: Ensure it meets needs

- Evolution: Adapt to changes

- Common Process Models:

- Waterfall, Prototyping, Spiral, Iterative

Software Process Models

1. Waterfall Model

- Concept: Sequential phases with sign-off before moving to the next stage.

- Phases:

- Requirements definition

- System/software design

- Implementation & unit testing

- Integration & system testing

- Operation & maintenance

- Advantages: Structured, easy to manage, quality control at each stage.

- Drawbacks:

- Early freezing of requirements/design leads to mismatches with user needs.

- Inflexible partitioning can produce unusable systems.

- Requirement gathering is difficult and prone to change.

2. Prototyping Model

- Concept: Iterative creation of partial system versions to refine requirements.

- Process: Requirements gathering → Quick design → Build prototype → Customer evaluation → Design refinement → Full development.

- Advantages: Improves requirement accuracy, engages users early.

- Drawbacks:

- Prototypes often discarded (wasted work).

- Incomplete prototypes may miss critical requirements.

- Risk of over-refinement ("creeping excellence").

- Variation: Evolutionary Prototyping – Gradually evolve prototype into final system.

3. Spiral Model

- Concept: Combines waterfall with continuous risk analysis and iteration.

- Four Steps per Cycle:

- Determine objectives, constraints, alternatives.

- Assess/reduce risks.

- Develop and validate.

- Review and plan next iteration.

- Advantages: Strong risk management, adaptable to project needs, high-quality results.

- Drawbacks:

- Heavy documentation and meetings (slow progress).

- More of a “meta-model” than a strict development method.

- Requires experienced team for risk analysis.

4. Iterative Development Model

- Concept: Build software in subsets, each adding critical features.

- Process:

- Start with key requirements and architecture.

- Develop subset product → Get feedback → Refine design and requirements → Add next subset.

- Advantages: Adapts to evolving customer needs, improves design through feedback.

- Drawbacks:

- Works best with small teams.

- Requires early architecture decisions, which are hard to change later.

3. Static Testing, RBT, and FMEA

Static Testing

- Reviews and analyses software documentation or code without execution, aiming to identify issues early when they are easier and cheaper to fix.

Manual Methods

- Informal reviews – casual peer review.

- Walkthroughs – presentation for feedback.

- Technical reviews – specialist checks.

- Inspections – formal, checklist-driven review.

- Audits – compliance verification.

Automated Methods

- Static Analysis – detects errors, vulnerabilities, quality issues.

- Lint Checks – enforce coding standards.

- Formal Methods – mathematical correctness proofs.

When Used, Focus Areas, Common Requirement Defects

- When Used: Throughout design, documentation, and development phases before dynamic testing.

- Focus Areas: Requirements, design documents, source code, and compliance with legal/security standards.

- Common Requirement Defects: Incompleteness, ambiguity, inconsistency, untestability, unfeasibility.

Risk-Based Testing (RBT)

- Testing that focuses on areas of highest risk to reduce overall project risk.

Risk Types & Benefit

-

Risk Types:

- Product risk – quality issues causing failures.

- Project risk – factors affecting project success (e.g., staffing, delays).

-

Benefits: Prioritises testing, supports contingency planning, improves productivity, and reduces costs.

Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA)

- Systematic technique to identify, prioritise, and mitigate potential failures before they occur.

- Failure Modes are the ways in which a design/ process/ system/ software might fail.

- Effects are ways these failures can lead to risks, e.g., waste, defects or harm.

Perform FMEA: Process Steps

- Define scope.

- Identify functions.

- Identify potential failure modes.

- Identify consequences.

- Rate severity (determine how serious the effect is).

- Calculate Risk Priority Number (RPN = Priority × Severity).

- Identify root causes.

- Recommend actions.

- Risk priority number (RPN) is used to quantify the overall ranking of risks (potential failure).

Failure Mode Types & Risk Categories

- Failure Mode Types: Loss of function, unintended function, delayed function, poor performance, incorrect value, support system failures.

- Risk Categories: System functionality, UI, transaction processing, performance, security, compliance, infrastructure, etc.

Potential Actions & Benefit

- Potential Actions: Remove requirement, add controls, quarantine risk.

- Benefits:

- No expensive tools required.

- Flexible for any project size.

- Helps prioritise changes.

- Supports building quality into products.

Relationship Between Static Testing & FMEA

- Static testing ensures clear, complete requirements.

- FMEA extends this by anticipating and ranking potential failures to guide dynamic testing priorities.

4. Black-box Testing

(Dynamic) Software Testing Life Cycle

- Software artifact

- Define test objectives.

- Design test cases.

- Develop test scripts.

- Run test scripts.

- Evaluate results.

- Generate feedback and change system.

- Regression testing.

Systematic Testing

- Explicit discipline for creating, executing, and evaluating tests.

- Recognizes complete testing is impossible; uses chosen criteria.

- Must include rules for test creation, completeness measure, and stopping point.

Black-box Testing

- Based on functional specifications (inputs, actions, outputs).

- Occurs throughout the life cycle, requires fewer resources than white-box testing.

- Supports unit, load, availability testing; can be automated.

Advantages: independent of software internals, early detection, automation friendly.

Black-box Methods

a. Functionality Coverage

- Partition functional specs into small requirements.

- Create simple test cases for each requirement.

- Systematic but treats requirements as independent (not full acceptance testing).

b. Input Coverage

- Ensures all possible inputs are handled.

- Methods:

- Exhaustive: test all inputs (impractical for large domains).

- Input partitioning: group into equivalence classes (valid/invalid).

- Shotgun: random inputs.

- Robustness: boundary value analysis.

- Examples:

- Partition inputs into valid/invalid ranges.

- Create minimal test cases for each partition.

c. Robustness Testing

- Ensures program doesn’t crash on unexpected inputs.

- Focus on boundary values (e.g., empty file, stack full/empty).

- More systematic than shotgun.

d. Input Coverage Review

- Exhaustive impractical, input partitioning practical.

- Shotgun + partitioning increases confidence.

- Robustness complements other methods.

C. Output Coverage

- Tests based on possible outputs (instead of inputs).

- Harder: requires mapping inputs to outputs.

- Effective in finding problems but often impractical.

Methods:

- Exhaustive output coverage (test every possible output, feasible in some cases).

- Output partitioning: group outputs into equivalence classes (e.g., number of values, zeros present).

- Drawback: finding inputs to trigger specific outputs is time-consuming.

5. White-box Testing

Whitebox Testing & Code Injection

Whitebox Testing

- Category: test perform in a lower level, concentrates on actual code, done by Developers or Testers

- Uses knowledge of a program’s internal structure to verify its logic, flow, and functionality by systematically covering code paths.

Testing Types

- Code Coverage: Tests ensure every method, statement, or branch runs at least once.

- Mutation Testing: Creates modified code versions to check if tests detect changes.

- Data Coverage: Focuses on testing the program’s data handling rather than control flow.

Code Injection

- Make code testing more efficient; generate copy of the code to test.

- Common approaches include:

- Action Instrumentation: Logs execution for coverage.

- Performance Instrumentation: Records time and resource usage.

- Assertion Injection: Validates program state at runtime.

- Fault Injection: Simulates failures to test fault handling.

Whitebox Testing Techniques

Code Coverage Methods

- Statement Coverage: Ensures every line of code executes at least once.

- Basic Block Coverage: Ensures each block of statements that always execute together is tested.

- Decision Coverage: Ensures each decision (e.g., if/else, switch) is evaluated both true and false.

- Condition Coverage: Ensures each condition within a decision is tested for both true and false.

- Loop Coverage: Ensures loops are tested with zero, one, two, and many iterations.

- Path Coverage: Ensures all possible execution paths in the control-flow graph are tested.

6. Whitebox Testing Techniques

Mutation Testing

Mutation Testing

- Purpose: Measures how effective a test suite is by introducing small faults (mutants) into the program.

- Process:

- Run the original program and fix any issues.

- Create mutants (one change each).

- Run test suite on mutants.

- If results differ → mutant is “killed” (detected). If not → tests are inadequate.

- Adequacy: Proportion of killed mutants to total mutants.

Systematic Mutation

- Requires rules for creating mutants and criteria for completion.

Common mutation types

- Value Mutation: Change constants or expressions

(e.g., 0 → 1, x → x+1). - Decision Mutation: Invert conditions

(e.g., == → !=, > → <). - Statement Mutation: Delete, swap, or duplicate statements.

Data Coverage

Data Coverage

- Focuses on how data is used and moves through a program

Data Flow Coverage

- Concerned with variable definitions:

- Variable definitions: variable is assigned a value

- Types of Variables:

- P-use: Predicate use (e.g., in conditions)

- C-use: Computation or output use

Data Flow Testing Strategies

- All-Defs: Every definition reaches at least one use.

- All P-Uses: Every definition reaches all predicate uses.

- All C-Uses: Every definition reaches all computation uses.

- All-Uses: Every definition reaches all predicate and computation uses.

7. Integration and System Testing

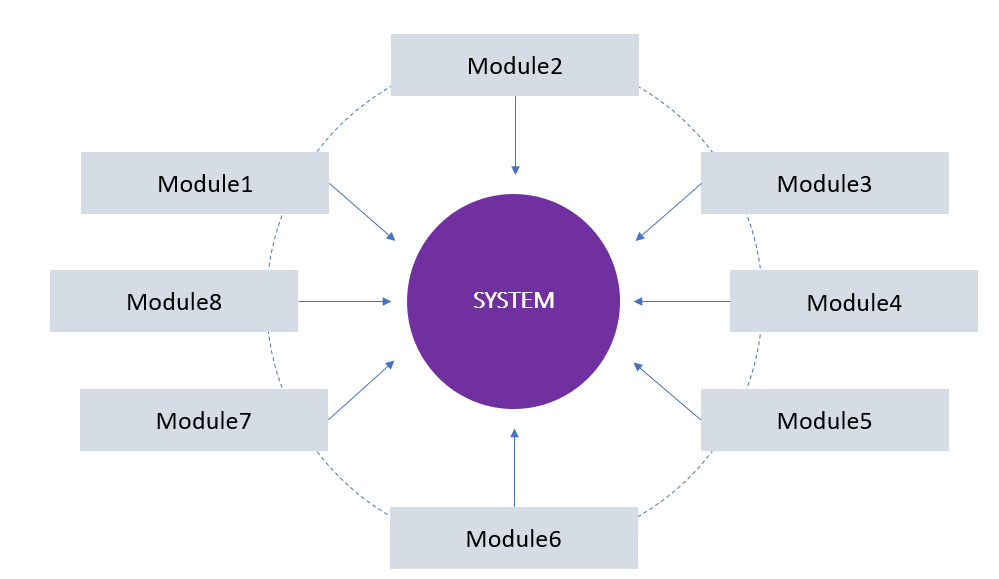

Integration Testing

-

Software Integration:

- Software is built as a collection of subsystems and modules.

- Each module is first tested individually (unit testing) and then combined into the complete system.

- Integration ensures that combined parts work as one system.

-

Integration Testing:

- Verifies that modules, subsystems, or applications work together correctly.

- Identifies issues such as compatibility errors, performance problems, data corruption, or miscommunication.

- Considered complete when:

- The system is fully integrated.

- All test cases are executed.

- Major defects are fixed.

- Why it matters: It ensures requirements are met, catches coding and compatibility issues early, and increases confidence in system quality.

Advantages and Challenges

- Advantages:

- Detect and fix defects early.

- Get faster feedback on system health.

- Flexible scheduling of fixes during development.

- Challenges:

- Failures can happen in complex ways.

- Testing may begin before all parts exist.

- Requires stubs (fake modules) or drivers to simulate missing modules.

- Granularity in Integration Testing:

- Intra-system testing: Combining modules within one system (main focus).

- Inter-system testing: Testing across multiple independent systems.

- Pairwise testing: Testing two connected systems at a time.

Integration Strategies

- Big Bang: All modules are integrated and tested together (at once).

-

- Convenient for small systems.

- Hard to locate faults, risky for large systems.

-

- Incremental Integration: Modules are tested and added one by one.

- Early fault detection.

- Needs planning, more cost.

- Two forms:

- Bottom-up: Start from lower-level modules using drivers.

- Top-down: Start from top modules using stubs.

- Sandwich: Mix of both, testing top and bottom simultaneously until meeting in the middle.

System Testing

-

System testing:

- Black-box testing of the fully integrated system.

- Ensures the system meets customer requirements and is ready for end-users.

- Tests both functional (tasks) and non-functional (performance, reliability, usability, security) requirements in realistic environments.

-

Scope of System Testing

- Covers:

- Functional correctness.

- Interfaces and communication.

- Error handling.

- Performance and reliability.

- Usability.

- Security.

- Examples:

- E-commerce website (login, cart, payment).

- Car systems (engine, brakes, fuel system).

- Online shopping site (integration bugs like missing discounts or wrong shipping).

- Covers:

Pros and Cons of System Testing

- Advantages:

- Detects most faults before acceptance testing.

- Builds user and developer confidence.

- Tests system in production-like conditions.

- Disadvantages:

- Time-consuming.

- Hard to isolate the exact cause of errors.

8. Testing Automation Selenium

Selenium

- Selenium is primarily used for automated testing of web applications.

- Instead of manually clicking, typing, or navigating in a browser, Selenium scripts simulate these actions automatically.

Key Capabilities

- Automates user interactions with web applications (typing, clicking, selecting, navigating).

- Provides cross-browser and cross-platform compatibility (Chrome, Firefox, Safari, Edge; Windows, macOS, Linux).

- Offers extensibility through plugins and integrations.

Types of Tests with Selenium

- Functional Tests – Verify new features and functionality.

- Regression Tests – Ensure new code changes don’t break existing features.

- Smoke Tests – Check if a new build is stable for further testing.

- Integration Tests – Validate that modules work together as expected.

- Unit Tests – Developer-written tests for individual code components.

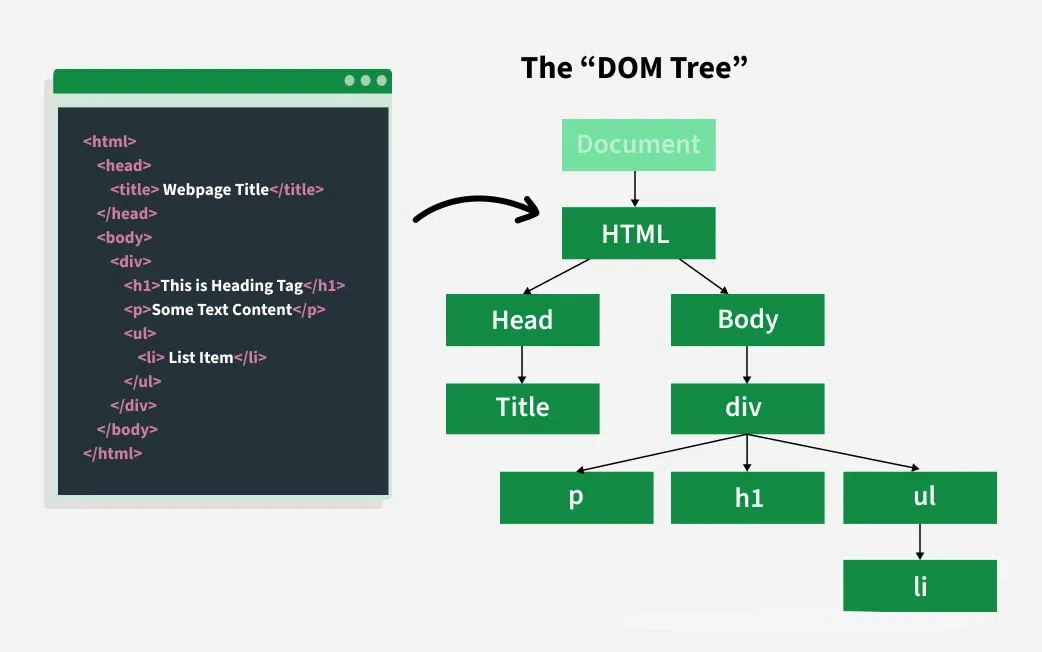

DOM

- Selenium interacts with HTML elements using the Document Object Model (DOM).

- Common element locators: ID, name, class name, tag name, CSS selector, XPath, link text, and partial link text.

- Supports advanced interactions such as handling forms, dropdowns, alerts, and taking screenshots.

Example of DOM

How Selenium Interacts with DOM

- Using Selenium, you can locate and manipulate these elements:

Example in python

from selenium import webdriver

from selenium.webdriver.common.by import By

driver = webdriver.Chrome()

driver.get("https://example.com")

# Find elements using DOM

title = driver.find_element(By.ID, "main-title") # Locate <h1>

username_box = driver.find_element(By.NAME, "username") # Locate input field

submit_button = driver.find_element(By.ID, "submit-btn") # Locate button

# Interact with elements

username_box.send_keys("TestUser")

submit_button.click()

driver.quit()

- Here, Selenium uses DOM locators (

ID,Name) to find and interact with page elements just like a user would.

9. Testing Automation

TestCafe

TestCafe

-

Overview:

- Node.js-based, open-source framework for end-to-end web application testing.

- Released in 2016 as a simpler alternative to Selenium.

-

Architecture:

- Proxy-based model with Node.js server and client-side browser scripts.

- Executes directly in browsers, no WebDriver required.

-

Strengths:

- Easy setup and zero configuration.

- Cross-browser and cross-platform support (desktop, mobile, cloud).

- Parallel test execution and automatic waiting.

- Built-in reporting, debugging, and cloud integration.

-

Limitations:

- Only supports JavaScript/TypeScript.

- CSS selectors only (XPath requires workarounds).

- Requires third-party integrations for mobile testing.

- Potential performance issues with large test suites.

-

Setup Process:

- Install Node.js, set up IDE (e.g., VS Code), install TestCafe via npm.

- Write scripts using fixtures, tests, and hooks.

-

Core Features:

- Selectors: CSS-based element targeting.

- Actions: Simulate user interactions (click, type, drag, navigate, etc.).

- Assertions: Validate expected outcomes using

t.expect.

-

Example:

- Fill out a form → Click submit → Assert greeting message matches expectation.

10. AI-Assisted Testing

Behaviour-driven development (BDD) and Cucumber

-

BBD:

- Definition: BDD is a modern software-development approach that helps teams describe what a system should do in simple everyday language.

- Goal: To make sure developers, testers, and business people all understand the same thing before the software is built.

- How it helps: Everyone can read the same descriptions (called scenarios), so there’s less confusion and fewer bugs.

- Main tool: Cucumber — it reads those descriptions and automatically checks if the program behaves as described.

-

Cucumber:

- How cucumber works:

- You write your test in plain text, such as:

- How cucumber works:

Scenario: Breaker guesses a word

Given the Maker has chosen a word

When the Breaker makes a guess

Then the Maker is asked to score

- Each Scenario shows a small example of how the system should behave.

- Cucumber connects each sentence (“Given…”, “When…”, “Then…”) to code that runs automatically.

- After running the tests, Cucumber tells you which scenarios passed or failed.

Gherkin Syntax (the Language of Cucumber)

- Gherkin is a special, easy-to-read format used by Cucumber.

- Each file (called a feature file) describes one feature of the system.

- Gherkin uses these main keywords:

- Feature: a short summary of what’s being tested.

- Scenario: a single example of a situation to test.

- Given: what the starting situation is.

- When: what action happens.

- Then: what the expected result is.

- And / But: used to connect extra steps.

- Feature: Login Function

Scenario: Successful login

Given the user opens the login page

When they enter a valid username and password

Then they should see the homepage

Step Definition (Connecting to Code) and Step Data (Extra Test Information)

- Step Definition:

- The sentences in your .feature file don’t run on their own.

- Each step is linked to a piece of code called a step definition.

- For example (Python):

from behave import given, when, then

@given('the user opens the login page')

def step_impl(context):

# Code to open the login page

pass

-

Cucumber finds the right code for each step and runs it during testing.

-

Step Data:

- Sometimes a step needs extra data, like text or a table:

- Text block:

- → In Python, you can read it with context.text.

"""

This is a block of text attached to a step.

"""

- Table of data:

- → In Python, use context.table to access it.

| name | department |

| Barry | Beer Cans |

| Pudey | Silly Walks |

How to Start Using Cucumber

- Step 1 – Install Tools

- Install Cucumber, a text editor (like VS Code), and a browser automation tool such as Selenium.

- Choose a programming language (Python, Java, etc.).

- Step 2 – Write Scenarios

- Create a folder called features, then a file such as tutorial.feature that contains your scenarios written in Gherkin.

- Step 3 – Write Step Definitions

- In a folder called features/steps, create a Python file such as tutorial.py with your code for each step.

- Step 4 – Run the Tests

- Open your terminal, go to your project folder, and type:

behave

- Cucumber will run the tests and show which ones passed or failed.